Revisione strumentale per una corretta postura nella pratica clinica dell’igienista dentale

D. Rotundo RDH* P.P. Forte T.O. ** A. Butera RDH***

Introduzione

Lo scopo di questa revisione è spiegare il modo in cui diverse procedure professionali possono essere eseguite nella bocca del paziente mantenendo una sana e corretta postura seduta. Il modo in cui le condizioni per adottare questa postura devono essere applicate è mostrato con l’aiuto delle fotografie. Al fine di chiarire meglio questi concetti, sono inclusi molti esempi dei modi in cui è possibile lavorare in una posizione eretta simmetrica senza sovraccaricare le strutture muscolo-scheletriche. Adottare questa postura previene l’alta percentuale di disturbi muscolo-scheletrici che sono noti affliggere circa il 65% degli igienisti e sono inoltre causa di una alta percentuale di disabilità. Nel documento “Indicazioni ergonomiche per attrezzature dentali” sono specificati i principi per progettare riuniti dentali appropriati per lavorare in modo sano.

Questi principi sono derivati da:

ISO Standard 6385 “Ergonomic principles in the design of work systems”.

ISO Standard 11226 ”Ergonomics – Evaluation of static working postures”.

Working postures and Movements. Tools for Evaluation and Engineering. Editors: Delleman NJ, Haslegrave CM and Chaffin DB. New York, Washington: CRC Press

LLC, 2004.

Physical workload in neck, shoulders and wrists/hands in dental hygienists during a work-day.

Abstract (1)

Physical workload was recorded by electromyography, inclinometry and goniometry for twelve female dental hygienists during authentic work. Their work was, in relation to other types of work, characterised by pronounced head flexion (90th percentile 46°), high loads on the forearm extensor muscles (90th percentile 23% and 18% of maximal EMG (MVE), for the right and left sides, respectively), average loads on trapezius muscles (90th percentile 15% and 14% MVE), average arm elevation (99th percentile 83° and 72°) and average wrist flexion and velocities (50th percentiles 17° of extension and 7.3°/s, for the right side). Manual scaling and machinery (use of ultrasonic scaling and hand-pieces) showed higher loads on the trapezius muscles, regarding muscular rest, as well as the 10th and 50th percentiles, than the other tasks, and for the forearm extensor muscles, an almost complete lack of muscular rest (0.1% time), and much higher loads regarding the 10th and 50th percentiles. Further, more pronounced head flexion and lower head and upper arm velocities were found, indicating more constrained postures for the neck and shoulders for the manual scaling and machinery. Use of ultrasonic scaler reduced the 50th percentile loads on the right forearm extensor muscles, but had no effect on the fraction of muscular rest and on the 10th percentile load. These findings are consistent with the high prevalences of musculoskeletal disorders among dental hygienists.

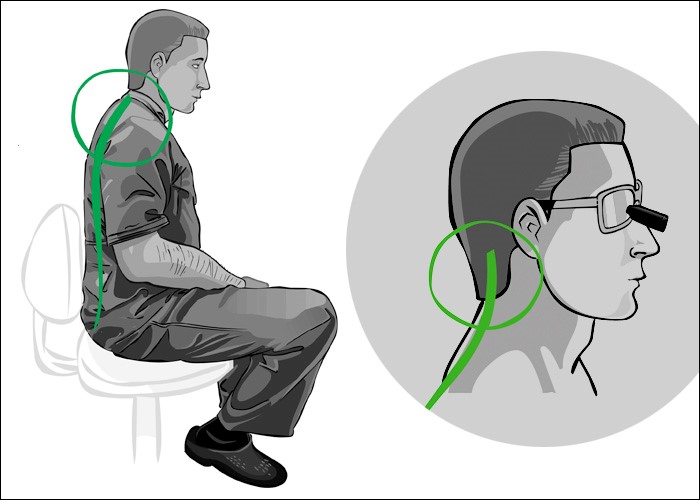

Sedere in una posizione eretta, rilassata e simmetrica con le braccia contro il tronco, il che minimizza il carico statico delle braccia e delle spalle. Inoltre, i movimenti delle braccia sia lateralmente sia in avanti devono essere il più possibile ridotti, lateralmente entro 15-20° e in avanti entro 25°. Il tronco può essere piegato in avanti rispetto all’articolazione delle anche fino a un massimo di 10-20°, ma si dovrebbe evitare di piegarsi di lato/lateralmente e di ruotare.

La testa può essere piegata in avanti un massimo di 25°. Lavorare in modo dinamico, facendo il massimo numero possibile di movimenti con il corpo durante il trattamento del paziente, in modo che si verifichi un’alternanza di carico e rilassamento nei muscoli e nella colonna vertebrale. Assicurarsi una robusta muscolatura del busto tramite sport o movimenti al di fuori delle ore di lavoro, in modo che i muscoli caricati possano recuperare e aumentare la forza muscolare, il che a sua volta permette di riuscire meglio a mantenere una postura corretta.

Adottare una postura seduta stabile e attiva.

Per adottare una postura seduta stabile e attiva, da cui eseguire facilmente i movimenti, l’operatore siede simmetricamente eretto, con lo sterno spinto leggermente in avanti e verso l’alto e i muscoli addominali leggermente sotto sforzo. Le spalle sono al di sopra dell’articolazione delle anche e la linea di gravità corre attraverso le vertebre lombari e la pelvi in direzione della seduta. Questa postura facilita una corretta respirazione.

(2) Disability self-assessment and upper quarter muscle balance between female dental hygienists and non-dental hygienists.

Abstract

PURPOSE:

The purpose of this pilot study was to compare disability self-assessment and upper quarter muscle balance female dental hygienists and non dental hygienist females. The upper quarter was operationally defined as the shoulder and neck region. Muscle balance was operationally defined as muscle flexibility and muscle performance.

METHODS:

A convenience sample of 41 working dental hygienists and 46 non dental hygienists participated in the study. Muscle flexibility of the upper quarter was measured by inclinometry or standard muscle length testing. Muscle performance was measured by timing the duration of four statically maintained positions. Subjects filled out the Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire (NPNPQ), which is a disability self-assessment. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used during data analysis to adjust for the mean age difference between the dental hygienist group (38.0 years) and the non-dental hygienist group (29.3 years).

RESULTS:

The results of this pilot study suggest that female dental hygienists are more likely than non dental hygienist females to develop tightness in the upper trapezius (p = 0.007) and the levator scapula (p = 0.01) of the non dominant upper quarter and lower fibers of the pectoralis major of the dominant upper quarter (p = 0.03) Muscle performance trends in the dental hygienist group supported muscle balance theory that short muscles remain strong while lengthened muscles become weak. The dental hygienist group had higher disability scores in all nine parts of the NPNPQ compared to the non-dental hygienist group, five of which were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

CONCLUSION:

The results of this pilot study suggest that muscle imbalances in the upper quarter are more common in female dental hygienists than in female non dental hygienists and may contribute to the numerous upper quarter pathologies associated with the practice of dental hygiene. Further research is needed to determine if upper quarter strengthening and flexibility exercises performed by dental hygienists can reduce disability self-assessment.

Condizioni per ottenere una postura di lavoro ottimale.

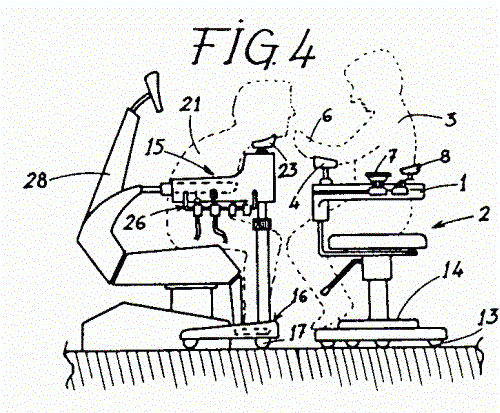

Le condizioni per ottenere una postura di lavoro stabile e ottimale sono le seguenti: Sedere in una posizione di lavoro eretta stabile. Porre il campo di lavoro nel cavo orale proprio davanti al torso nel piano simmetrico. Questo è il piano mediano sagittale che divide verticalmente il corpo in due parti uguali. Guardare il più possibile perpendicolarmente al campo di lavoro. Se questo non avviene i globi oculare pilotano la testa fino a che essa raggiunge questa posizione, e allora la postura del corpo cambia automaticamente. In questo modo i globi oculari arrivano alla posizione di guardare il più possibile perpendicolarmente al campo di lavoro.

Ogni volta che il campo di lavoro giace al di fuori del piano simmetrico, questo porta ad una sfavorevole postura piegata che è asimmetrica, e ciò accade frequentemente. Si può confrontare la posizione del campo di lavoro nel cavo orale del paziente con la posizione in cui si tiene una mela mentre la si sta pelando oppure un ago quando ci si prepara ad infilarlo: si tengono questi oggetti davanti al tronco senza piegare la testa. Inoltre, la posizione obliqua in cui si tiene un libro quando si sta seduti su una sedia a leggere (con la lampada di lato/dietro di sé) dà un’idea di come piazzare il campo di lavoro in modo da essere in grado di guardarlo perpendicolarmente.

Girando la testa del paziente nei tre piani dello spazio è possibile porre il campo di lavoro nel piano simmetrico dell’operatore, e la superficie del dente trattato deve essere girata verso la direzione della visione. In altre parole, questa superficie è posizionata parallela al lato frontale della testa dell’igienista.

(3) Effect of magnification loupes on dental hygiene student posture.

Abstract

The chair-side work posture of dental hygienists has long been a concern because of health-related problems potentially caused or exacerbated by poor posture. The purpose of this study was to investigate if using magnification loupes improved dental hygiene students’ posture during provision of treatment. The treatment chosen was hand-scaling, and the effect of the timing of introduction of the loupes to students was also examined. Thirty-five novice dental hygiene students took part in the study. Each student was assessed providing dental hygiene care with and without loupes, thus controlling for innate differences in natural posture. Students were randomized into two groups. Group one used loupes in the first session and did not use them for the second session. Group two reversed this sequence. At the end of each session, all students were videotaped while performing scaling procedures. Their posture was assessed using an adapted version of Branson et al.’s Posture Assessment Instrument (PAI). Four raters assessed students at three time periods for nine posture components on the PAI. A paired t-test compared scores with and without loupes for each student. Scores showed a significant improvement in posture when using loupes (p<0.0001), and these improvements were significantly more pronounced for students starting loupes immediately on entering the program compared with students who delayed until the second session (p<0.1). These results suggest a significant postural benefit is realized by requiring students to master the use of magnification loupes as early as possible within the curriculum.

(4) Postural changes in dental hygienists. Four-year longitudinal study.

Abstract

Numerous surveys identify the occurrence of musculoskeletal complaints as a concern in dentistry. However, no longitudinal data exist to indicate whether postural changes occur as a result of practicing dental hygiene. The purpose of this preliminary, four-year longitudinal study was to investigate whether any postural changes developed during the hygienists’ clinical education and/or during subsequent dental hygiene practice after one and/or two years. It was anticipated that the awkward positions and intense physical demands placed on hygienists might initiate musculoskeletal problems, but that no postural changes would occur over this short period of time. Nine of 10 dental hygienists in the graduating class of 1987 were surveyed for existing musculoskeletal complaints, and the subjects were photographed for a measurement of postural change. Responses from participants indicated an increase in musculoskeletal-related complaints in each of the six areas investigated. The photographic findings indicated that one of the nine hygienists showed an increase in forward head posture, a postural change.

Guardare perpendicolarmente il campo di lavoro è come

leggere un libro.

Altezza del campo di lavoro: il posto per maneggiare gli strumenti nel cavo orale.

Gli avambracci sono alzati di 10-25°.

Caratteristiche di una posizione sana ottimale.

Sedere il più indietro possibile sulla seduta per ottenere una postura stabile, simmetricamente eretta. Le braccia devono stare lungo il tronco per sostenere gli avambracci mentre eseguono il trattamento. L’angolo tra cosce e gambe deve essere 110° o leggermente superiore, con le gambe leggermente divaricate.

Regolare correttamente l’altezza di lavoro, con gli avambracci un po’alzati, da 10° fino a un massimo di 25°. La distanza tra il campo di lavoro nel cavo orale e gli occhi o gli occhiali di solito è tra 35-40 cm. La schiena deve essere sostenuta nel punto superiore/posteriore della pelvi in modo che non appena i muscoli diventano troppo stanchi per mantenere una posizione eretta della schiena, il poggia-schiena fa in modo che la posizione eretta desiderata possa essere mantenuta.

Questo sostegno deve verificarsi senza pressione sui muscoli al di sotto e al di sopra di questo punto, perché la postura viene sfavorevolmente nfluenzata da questo, e si ha una riduzione dei movimenti. Gli strumenti sono maneggiati con la presa a penna modificata, con le prime 3 dita piegate in forma arrotondata intorno allo strumento e le altre 2 dita che si appoggiano in modo stabile dentro o fuori dal cavo orale.

(5) The effects of periodontal instrument handle design on hand muscle load and pinch force.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In comparison with people in other occupations, dentists and dental hygienists are at increased risk of developing work-related musculoskeletal disorders, including carpal tunnel syndrome. An important risk factor in dental practice is forceful pinching, which occurs duringdental scaling. Ergonomically designed dental instruments may help reduce the prevalence of MSDs among dental practitioners.

METHODS:

In the authors’ study, 24 dentists and dental hygienists used 10 custom-designed dental scaling instruments with different handle diameters and weights to perform a simulated scaling task. The authors recorded the muscle activity of two extensors and two flexors in the forearm with electromyography, while thumb pinch force was measured by pressure sensors.

RESULTS:

Handle designs of periodontal instruments had significant (P < .05) effects on hand muscle load and pinch force during a manual scaling task. The instrument with a large diameter (10 millimeters) and a light weight (15 grams) required the least amount of muscle load and pinch force. There was a limit to the effect of handle diameter, with diameters larger than 10 mm having no additional benefit; however, the study did not identify a limit to the effect of reducing the weight of the instrument, and therefore instruments lighter than 15 g may require even less pinch force.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS:

The results from this study can guide dentists and dental hygienists in selection of dental scaling instruments.

(6) Comparison of muscle activity associated with structural differences in dental hygiene mirrors.

Abstract.

PURPOSE:

Ergonomic studies suggest that the commonly used pinch grasp, held in a static position, is a contributing factor for dental Hygienists’ development of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) such as carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), Trigger Thumb, de Quervain’s stenosing tenosynovitis, and carpometacarpal (CMC) osteoarthritis. The pinch grasp is commonly used by the dental hygienist while holding the dental mirror in the non-dominant hand. In response to this concern, manufacturers are redesigning dental mirror handles. The value of these re-designed products is based solely on anecdotal evidence. To date, minimal research has been done to examine the non-dominant mirror hand. The purpose of this study was to objectively evaluate dental mirror handle design using surface electromyography (sEMG) to compare muscle activity associated with grasping the mirror.

METHODS:

This randomized controlled clinical trial utilized a two-by-two repeated measures statistical design. Data was collected on a convenience sample of 19 (N=19) healthy dental hygiene students in their last year of study. Data collection was divided into two phases to maintain a balanced study. The independent variables in phase I were diameter and weight. The independent variables in phase II were weight and padding. Muscle activity was measured while grasping various dental hygiene mirrors in 30-second increments using sEMG. Following data collection subjects designated which mirror felt most and least comfortable to compare subjective data with objective data.

RESULTS:

Three statistically significant results occurred. In phase II, padding (p=.01) demonstrated the largest reduction of muscle activity in the flexor pollicis brevis, by decreasing mean muscle activity by 3.7 microv. The interaction of diameter and weight (p=.01) in phase I reduced the mean muscle activity in the extensor digitorum by .8 microV and weight (p=.02) in phase II decreased the muscle activity in the extensor digitorum by .62 microV. Self-reports of comfort reported by the subjects in this study were not consistent with the measurements of muscle activity using sEMG.

CONCLUSION:

Ergonomic adaptations to dental hygiene mirror handles were associated with increases and decreases in muscle activity. The clinical impact of this is amplified as force is exerted. Furthermore, it may be possible to reduce WMSDs for dental hygienists by using instrument designs during the workday. Self-reports of comfort by the subjects in this study did not calibrate with the measurements of muscle activity using sEMG. Additional research is needed to further isolate the external variables of the study and to determine what actual reduction in muscle activity is significant for maintaining musculoskeletal health.

Sgabelli di lavoro per l’igienista.

L’angolo minimo tra la coscia e la gamba del dentista seduto deve essere 110°.

Questo richiede un disegno della seduta che differisce dalla tradizionale seduta quasi orizzontale. Le

dimensioni del sedile devono rendere possibile sedere senza pressione sia sul deretano sia sulle

cosce. La seduta è quindi suddivisa in due parti per ottenere una postura seduta equilibrata: una parte

posteriore orizzontale per sostenere le natiche con una lunghezza minima di 15 cm e una parte

obliqua inclinata di 20° per un pari sostegno delle cosce inclinate. Con una parte frontale regolabile,

diventa possibile un angolo superiore a 110° fra cosce e gambe.

Si può usare una leggera inclinazione in avanti della seduta di massimo 6-8°. I bordi della seduta non dovrebbero essere rialzati, perché in questo modo i lati delle natiche con i loro muscoli sono sollevati verso l’alto e questo riduce la stabilità della pelvi. La massima profondità della seduta deve essere 40 cm e la larghezza 40 cm con un massimo di 43 cm. L’altezza minima della seduta della seduta (premuta) per un dentista alto 156 cm (P(F)5)* è 47 cm. L’altezza massima della seduta (premuta) per un’igienista alto 196 cm (P(M)95)* è 63 cm. Il range di aggiustamento della seduta dovrebbe essere tra 47 e 63 cm.

Al fine di sostenere la colonna vertebrale è necessario uno schienale con un sostegno lombare o pelvico alto da 10 a 12 cm all’estremità superiore della parte posteriore della pelvi che sia regolabile verticalmente da 17-22 cm e per dentisti molto alti fino a 24 cm. Il poggiaschiena con un sostegno lombare o pelvico deve essere regolabile anche orizzontalmente in modo da mantenere la curva più o meno concava (lordosi) della schiena, così che sia impossibile che la schiena adotti una forma a C, cioè una schiena arrotondata verso il dietro.

È possibile sedere eretti in una posizione seduta attiva ma non appena i muscoli sono stanchi la schiena si arrotonda, cosicché il supporto della pelvi è necessario per rimanere seduti eretti. Mentre si sta seduti in una posizione di lavoro, non vi dovrebbe essere contatto tra lo schienale e la muscolatura della schiena su entrambi i lati del sostegno pelvico/lombare perché questo disturba una buona posizione seduta. Ma per stirarsi, rilassarsi, o appoggiarsi all’indietro lo schienale può continuare verso l’alto, e anche un po’ all’indietro, cosicché il contatto può avvenire con la schiena appoggiandosi all’indietro.

Il poggiaschiena con il sostegno pelvico non dovrebbe essere più largo di 30 cm. Il poggiaschiena è elastico su una breve distanza di 1-2 cm e può ruotare intorno ad un asse orizzontale con un angolo di 25° verso l’alto e verso il basso; mentre l’imbottitura dovrebbe essere sufficientemente comprimibile da tollerare di essere schiacciata per adattarsi alla curvatura individuale della schiena.

La tappezzeria della seduta deve essere sufficientemente dura con una superficie irruvidita. Deve essere rigida e schiacciarsi solo leggermente. Una imbottitura troppo soffice permette alla pelvi di arrivare ad una posizione scorretta e instabile ed è stancante. Una superficie liscia fa scivolare via. Se si desiderano i braccioli, sono necessari due braccioli, regolabili in modo continuo.

Nelle “Indicazioni ergonomiche per attrezzature dentali” i dati riguardanti la donna dentista P5 (P(F)5) alta 156 cm e l’uomo dentista P95 (P(M)95) alto 196 cm sono usati come valori limitanti. Questo significa che donne dentiste più basse di 156 cm e dentisti più alti di 196 cm non sono ancora considerati nell’ambito dei requisiti per la costruzione di attrezzature dentali.

(7) Work load, fatigue, and pause patterns in clinical dental hygiene.

Abstract

PURPOSE:

Previous studies have suggested that high frequencies of shoulder and neck complaints in dental hygienists mainly were due to longstanding, low-level static load of the neck and shoulder muscles. The purpose of the present study was to make continuous recordings of myoelectric signals from the shoulder muscles of dental hygienists in order to assess static load.

METHODS:

Myoelectric signals were recorded from the right trapezius muscle of 10 Swedish dental hygienists during half of a normal working day. A portable system for collection and on-line processing of myoelectric signals was used. Signal parameters were obtained, indicating muscular load, fatigue, pause frequency, and pause duration, respectively. All measurements were referred to a resting value and a reference contraction value established with the hand loaded with a 0.5 kg weight at the beginning of the recording session.

RESULTS:

A static load of 50 to 100% of the reference contraction (0.5 kg hand load with raised arm) was found in the trapezius muscle. The median load for the whole group was 57% of the reference level. Group data analyses of frequency EMG seldom showed significant fatigue. At individual levels, however, it was possible to identify localized muscle fatigue and relate it to a specific work task. There were many short pauses with a duration of 1 to 2 seconds, but an almost total lack of pauses of a duration longer than five seconds.

CONCLUSIONS:

Individual dental hygienists exhibited significant muscle fatigue that might be related to development of work related myalgias of the shoulder muscles. Future study of muscle patterns and dental hygiene tasks may lead to improved work designs and patterns for dental hygienists.

Le calzature per mantenere una corretta postura devono avere una suola antiscivolo, un assorbimento dell’energia al tallone, leggera e confortevole, antistatico e resistente a idrocarburi, lavabile ed elettrostatico. Il tacco per un professionista uomo deve essere compreso tra 1,5 cm a 2,5 cm, invece per la donna 2,5 cm a 3,5 cm, rispettivamente per una conformazione anatomica differente, perché nella donna è grande e retroposto, quindi per bilanciarlo il tacco deve essere più alto.

Conclusioni

Come evidenziato dal documento proposto, e quindi estrapolato dagli articoli e documenti di settore, tutti i risultati di questo studio suggeriscono che gli squilibri posturali nella pratica dell’igienista dentale possono contribuire alle numerose patologie riscontrate nell’operatore. È stato ulteriormente dimostrato come l’utilizzo di ausili ortopedici mirati contribuisca notevolmente alla correzione o, ancor meglio, alla prevenzione di molti disordini. Ulteriori ricerche sono necessarie per determinare nuove tecniche posturali e ausili di maggior qualità per gli igienisti dentali così da ridurre sempre più le disabilità.

Bibliografia:

(1) Physical workload in neck, shoulders and wrists/hands in dental hygienists during a work-day.

Åkesson I, Balogh I, Hansson GÅ.

Appl Ergon. 2012 Jul;43(4):803-11. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2011.12.001. Epub 2011 Dec 28.

PMID: 22208356 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

(2) Disability self-assessment and upper quarter muscle balance between female dental hygienistsand non-dental hygienists.

Johnson EG, Godges JJ, Lohman EB, Stephens JA, Zimmerman GJ, Anderson SP.

J Dent Hyg. 2003 Fall;77(4):217-23.

PMID: 15022521 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

(3) Effect of magnification loupes on dental hygiene student posture.

Maillet JP, Millar AM, Burke JM, Maillet MA, Maillet WA, Neish NR.

J Dent Educ. 2008 Jan;72(1):33-44.

PMID: 18172233 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

(4) Postural changes in dental hygienists. Four-year longitudinal study.

Barry RM, Woodall WR, Mahan JM.

J Dent Hyg. 1992 Mar-Apr;66(3):147-50.

PMID: 1385625 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

(5) The effects of periodontal instrument handle design on hand muscle load and pinch force.

Dong H, Barr A, Loomer P, Laroche C, Young E, Rempel D.

J Am Dent Assoc. 2006 Aug;137(8):1123-30; quiz 1170.

PMID: 16873329 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

(6) Comparison of muscle activity associated with structural differences in dental hygiene mirrors.

Simmer-Beck M, Bray KK, Branson B, Glaros A, Weeks J.

J Dent Hyg. 2006 Winter;80(1):8. Epub 2006 Jan 1.

PMID: 16451762 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

(7) Work load, fatigue, and pause patterns in clinical dental hygiene.

Oberg T, Karsznia A, Sandsjö L, Kadefors R.

J Dent Hyg. 1995 Sep-Oct;69(5):223-9.

PMID: 9161224 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

Adottare una postura di lavoro sana durante il trattamento del paziente.

Prof Oene Hokwerda, Rolf de Ruijter, Sandra Shaw.

Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen 2006

Indicazioni ergonomiche per attrezzature dentali

Prof Oene Hokwerda, Joseph Wouters, Sandra Zijlstra-Shaw

2007

Ricerca

Categorie